Tom Robert's Story:

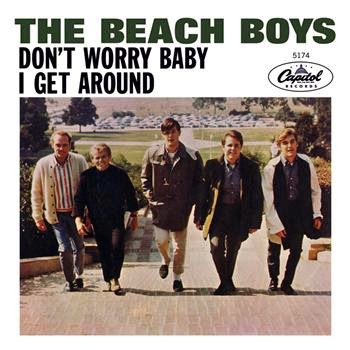

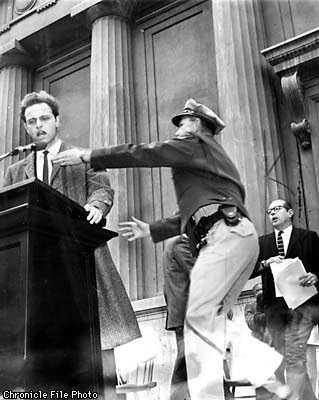

My senior year, I wanted to attend UC Berkeley, like my

idols Brian McGuire, Robert Gray and Mario Savio. However, my father—who had attended Berkeley

in the 30s—was of the opinion that there were three major centers of World

Communism: Moscow, Berkeley, and the

University of Chicago. So I went to St.

Mary’s College, where I signed up as pre-med and learned (1) to play rugby, (2)

to drink beer, and (3) that being color blind wasn’t a passport to success in

biology, chemistry, or the practice of medicine. (Doctor:

“Hmmm. Would you say that rash is

red or green or brown?” Patient: “Hmmm.

I’m going to give my lawyer a quick call.”)

Armed with a degree in Biology-Chemistry, I also learned

that no one in 1968 was anxious to hire someone with a 1-A draft

classification. Accordingly, I accepted

a position as a warehouseman at the Del Monte Cannery in Emeryville, where I

worked stacking boxes on the prestigious “glass line” (Fruits for Salad, very

special) until informed by my draft board in August 1968 that the enemy was

running critically short of targets, so that I would be snapped up in about six

weeks. Despite my best efforts, I

couldn’t find a reserve unit (the Coast Guard wouldn’t even put you on the wait

list if you over 17½).

As Brother Bernard, the typing guru, might have said: “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy

dog.” Arf.

So I was in the Army for three years, including a year in

Vietnam as a field artillery officer. My

brother Chris (class of 1968) came over while I was there; he flew intelligence

surveillance airplanes. We both came

home for a few weeks when our Dad died, then went back to finish our tours.

Returning to a Grateful Nation, I was unemployed for six

months—there was a recession, and the non-vets had all the jobs. My military skills of making beds, shining

shoes and directing artillery fire were not in the demand the recruiter had led

me to believe. Nevertheless, I was

eventually able to parlay my degree and my leadership background into a

position loading and unloading trucks at the post office in Oakland. Swing shift, 10% differential after

midnight—sweet!

After a year or so, I bid a fond adieu to my chums on the

loading dock and became a benefits counselor for the Veterans Administration,

first in San Francisco, then in San Diego.

It often pitted younger vets against the bureaucracy--like anything has

changed--and, was, somewhat to my surprise, very satisfying. During this period, my son Matthew was born.

In 1976, in a desperate bid to (1) get out of working, (2)

attend graduate school, and (3) avoid labs at all costs, I used the GI Bill and

enrolled at the University of Chicago Law School, thanks in large part to the

recommendation of Jim Burns, who had graduated a few years before. (His law license was eventually

restored.) Based on my father’s beliefs,

I fully expected to take courses with titles like, “Overthrowing the

Government: A Guide for Lawyers,” I was stunned to learn that the University

had since become the “crib” of Milton Friedman and the Trickle-Down

Quartet. Ah, the Great Mandala.

After graduation, I practiced law in Washington, DC, doing

mostly civil litigation and legislative law (lobbying). I was part of a team

representing an American company in the extremely famous “Polish Golf Car

Case,” in which we brought an action against a Polish company that had the

temerity to sell communist golf cars (not carts!) at a lower price than the

American kind—clearly a violation of the antitrust laws. (By the way, all possible jokes have been

made with regard to Polish golf cars.)

Legislative work was mostly in the tax area (although I did

work on the first Chrysler bailout in 1979-80).

I learned to say that, if Congress would just lower taxes for this particular

mega-corporation, the savings would be poured back into the economy to create

more jobs (primarily for the makers of cigarette boats, Rolex watches and

private jets).

On the other hand, I was also part of team that won a pro

bono case for some black iron workers against a discriminating union. That made us all feel like the license was

worth something.

I sort of burned out in DC and moved to Vermont, where I

practiced with a small firm. (Actually,

they are all pretty small.) Work was fun

and good, kind of like being in a real-life episode of Andy of Mayberry. The pay, however--not so much. I was a single dad at that point, and had to

worry about college for the boy--who else was going to guarantee my Golden

Years?

In 1987, I left Vermont to accept a position as General

Counsel on Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs, and have done legislative

stuff ever since. I was able to help

write and pass a lot of laws, including one that created a new Federal court

and another that changed the way the government pays for drugs. I once got lobbied by a guy from R.J.

Reynolds tobacco, who, in desperation, informed me that one was more likely to

get lung cancer from having a bird in the house (because of feathers or

something) than from cigarettes. Not

sure what would happen if one smoked the bird.

I “revolved” between the Congress and VA, at one point

working as Sen. Arlen Specter’s Chief Counsel and Staff Director. Arlen and I had kind of a stormy romance,

highlighted by me being fired at a Senate committee markup because I stood up

for the staff (firing later rescinded).

While working for the Senate, I also met my wife Jo, who was working for

Senator Alan Simpson. She later became a

judge at VA.

I left the Senate and became Chief Counsel for Legislative

Affairs at the Board of Veterans Appeals, part of VA, working there about nine

years. In 2003, following a more or less

“shot in the dark” job application, Jo and I moved to Germany where I became

the legislative counsel for the US European Command in Stuttgart, a “joint”

military headquarters with operational responsibility for US forces in Europe. I advise the command on what’s going on in

Congress, draft legislation, and coordinate lobbying efforts. Much fun.

Jo now holds the equivalent position at the US Africa Command, which is

also in Stuttgart.

We live in small town called Herrenberg (about 25 miles from

Stuttgart) and, frankly, would prefer not to leave. The pace is much less hurried, we are within

about two hours of five countries (we’ve literally gone to France and

Switzerland for lunch), stores aren’t open on Sunday, and Germans pretty much

love Americans. Plus, there’s no Second

Amendment.

Except now we have a grandson (4/16/14) who—as luck would

have it—is the most adorable baby in the history of the world. (What are the odds?) Baby and parents are in Austin, Texas, where

son Matthew manages people who do software development (I think), and his wife

runs the information technology stuff for a big home-sharing outfit. Austin has great music and horrible weather,

so we’ll see.

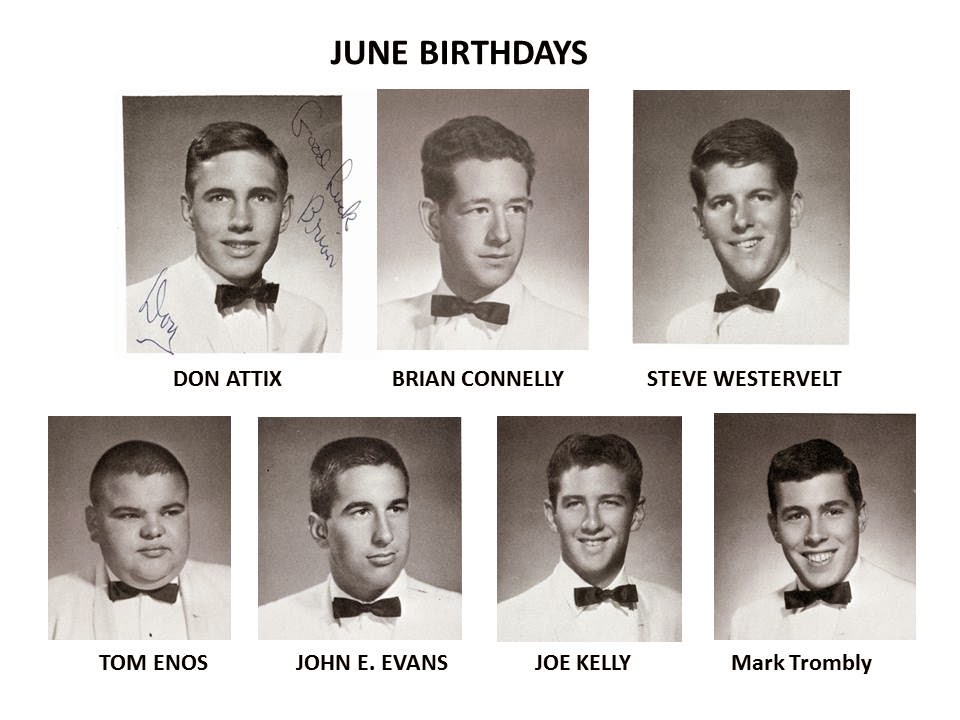

I keep trying to come up with “fond memories” of the high

school. Not sure if they’re fond, but here are four

things I remember, anyway:

1. Mr Neuberger,

explaining the importance of consistency in plotting a novel in English class,

telling us that you couldn’t have a story about a war hero with fabulous

exploits, and then have him slip on the gangplank and die when he gets off the

ship at home. Which is basically the

ending of the “Das Boot,” a great movie about a German submarine in WWII. (Should I have said “spoiler alert”?)

2. Football coach Dan

Shaughnessy telling us that “It’s no good unless it hurts.”

3. Brother Timothy,

on Friday, November 22, 1963, while we were in homeroom waiting to go to Mass,

coming into the classroom and saying:

“Now you have something to pray for.

President Kennedy’s been shot.”

4. Brian McGuire

telling me that I wrote as well as O. Henry.

See you soon.